- 1 Introduction

- 2 (B) Elements Present in IFRS but Absent in Japanese Standards

- 3 (C) Practical Expedients Specified in Japanese Standards but Not in IFRS

- 3.1 (1) Contract Modifications (Handling when immaterial)

- 3.2 (2) Identifying Performance Obligations (Handling when immaterial from the customer’s perspective)

- 3.3 (3) Performance Obligations Satisfied Over Time

- 3.4 (4) Performance Obligations Satisfied at a Point in Time

- 3.5 (5) Progress Measurement for Performance Obligations

- 3.6 (6) Allocating Transaction Price to Performance Obligations

- 3.7 (7) Combining Contracts, Identifying Performance Obligations, and Allocating Transaction Price

- 3.8 (8) Other Specific Issues

Contents

Introduction

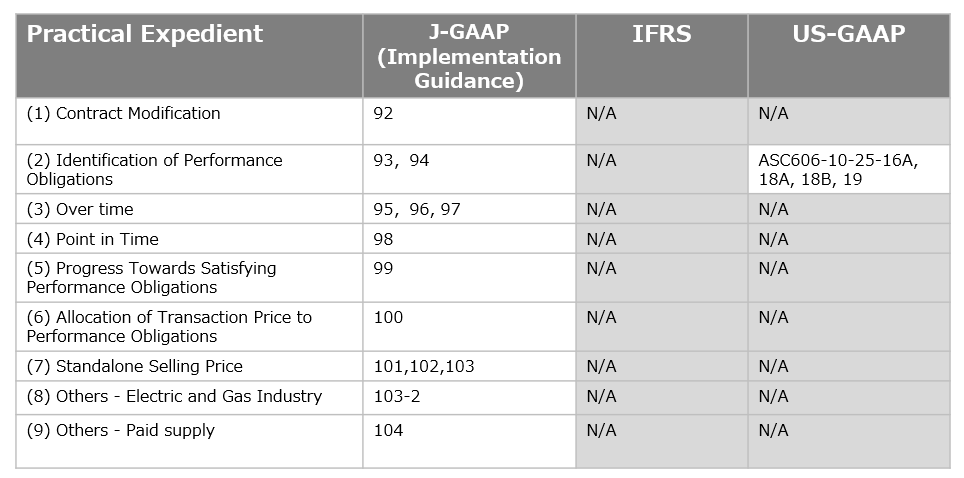

Starting from the beginning of the fiscal year and business year commencing on or after April 1, 2021, new revenue recognition standards equivalent to IFRS 15 and ASC 606 have been applied in Japan.

Per Accounting Standards for Revenue Recognition (ASBJ Statement No. 29) Paragraph 98, the concepts for this implementation are as follows:

1. Essentially adopt all provisions of IFRS 15.

2. Establish additional alternative treatments (practical expedient) to address application challenges, ensuring these do not significantly impair international comparability.

Per Accounting Standards for Revenue Recognition (ASBJ Statement No. 29) Paragraph 98,

Based on the above concepts, for those familiar with accounting standards other than Japanese standards, such as IFRS or US GAAP, please keep in mind the following two points when understanding revenue recognition under Japanese standards:

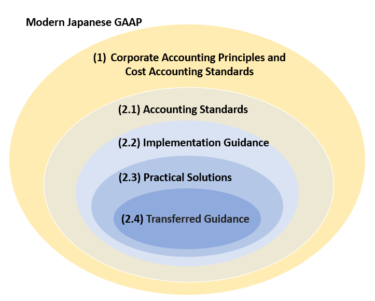

(A) Firstly, the Japanese revenue standards are almost identical to IFRS 15. The general content is similarly applicable, so please rest assured.

(B) However, there are parts present in IFRS 15 that are not included in the Japanese standards.

(C) Additionally, the Japanese standards include practical expedients, referred to as “alternative treatments.”

This can be illustrated with the following Venn diagram.

To aid the understanding of users of Japanese standards, I will delve deeper into points (B) and (C).

(B) Elements Present in IFRS but Absent in Japanese Standards

Key points of (B)

Firstly, the content of point (B) includes the following two aspects:

1. Treatment of contract costs (acquisition costs, fulfillment costs): These are required under IFRS but fall outside the scope of Japanese standards.

2. Selling/Disposal transactions of non-financial assets: IFRS 15 applies to these at the time of derecognition, while Japanese standards exclude them from the scope of accounting standards altogether.

These differences arise because the Japanese standards for capitalizing costs, such as inventories and fixed assets, differ from the IFRS framework. This divergence in accounting frameworks aims to avoid complexity.

However, despite these differences, it is believed that there will be no significant discrepancies in the outcomes when applying both standards.

Key Points on Contract Costs

However, there are three points to note regarding point 1:

a. Contract fulfillment costs are generally handled similarly, but acquisition costs are often expensed immediately under Japanese standards. However, IFRS/US-GAAP also permits immediate expensing of acquisition costs in certain cases, leading to similar accounting treatments.

b. Additionally, since contract costs fall outside the scope of Japanese standards, they are not disclosed. Therefore, users of financial statements need to be aware if they wish to use information on contract costs.

c. When Japanese companies applying IFRS or US GAAP to their consolidated financial statements adopt these Japanese standards for their individual financial statements, treating contract costs differently between consolidated and individual financial statements may impose a practical burden. Therefore, it is permissible to follow the contract cost provisions of IFRS 15 or FASB-ASC Subtopic 340-40 “Other Assets and Deferred Costs – Contracts with Customers” (hereafter “Subtopic 340-40”) in individual financial statements. This practical approach for companies preparing consolidated financial statements under standards other than Japanese standards is intended to avoid significant differences or investor misunderstandings.

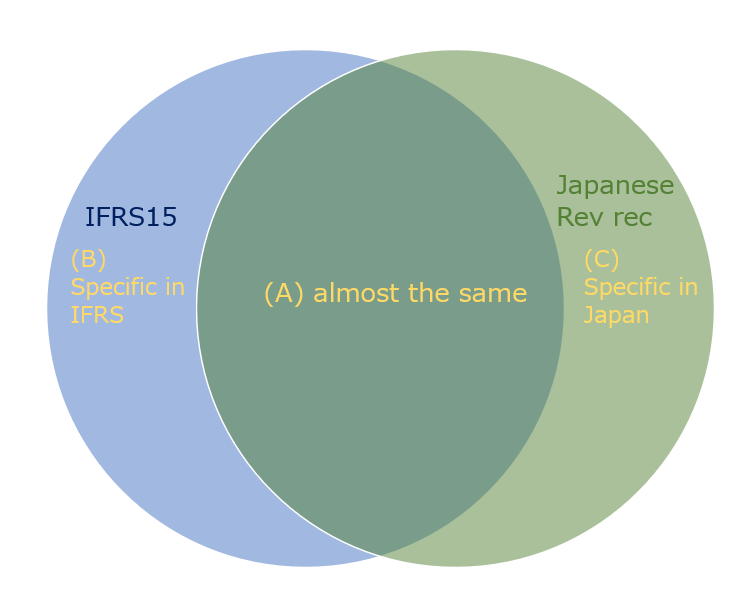

(C) Practical Expedients Specified in Japanese Standards but Not in IFRS

Next, we introduce the practical expedients specified in Japanese standards, which are not explicitly stated in IFRS.

First, please understand that these practical expedients are designed not to significantly impair international comparability. In other words, alternative treatments are permitted only for items of lesser importance or those expected to have minimal deviation from the principal treatment.

The necessity of these expedients arises from the need to consider existing Japanese practices when applying the new revenue recognition standards domestically. The new standards, like other imported accounting standards, adopt a more asset-liability (balance sheet) focused approach typical of Western perspectives, rather than the profit and loss (P&L) focus traditionally seen in Japan. This shift significantly impacted Japanese corporate accounting practices, prompting the need for these unique practical expedients to facilitate the transition smoothly.

However, it is essential to understand that these practical expedients are carefully balanced to avoid deviating too far from the principal treatments, thereby preserving comparability with IFRS and US GAAP. While IFRS and US GAAP also consider materiality and may employ similar approaches in practice, Japanese standards explicitly mention practical expedients in the official accounting guidelines. When applicable, it is crucial for preparers to actively consider these expedients from a cost-benefit perspective.

It is also recommended that companies confirm with their auditors whether the above items are considered immaterial.

Now, let’s examine the details.

(1) Contract Modifications (Handling when immaterial)

When the addition is immaterial compared to the existing contract, any of the following can be applied (Implementation Guidance 92):

1. Treat as a separate contract.

2. Assume the existing contract is terminated and a new contract is created.

3. Assume the modification is part of the existing contract.

Contract modifications can be a complex area in practice.

Spending time on immaterial modifications is something we want to avoid since the effort doesn’t yield significant results.

This alternative approach helps reduce the effort when the addition of goods or services is immaterial to the existing contract.

You can skip the cumbersome decision-making process and choose any of the three options.

(2) Identifying Performance Obligations (Handling when immaterial from the customer’s perspective)

– When immaterial from the customer’s perspective, you can choose not to evaluate whether the promise constitutes a performance obligation (Implementation Guidance 93).

For shipping and delivery activities performed after the customer gains control of the goods, you can choose not to identify these as performance obligations (Implementation Guidance 94).

This approach, recognized in US GAAP, is also adopted in Japanese standards.

First, consider immaterial performance obligations.

Contracts often include many promises, and multiple performance obligations may be identified.

However, some promises are clearly immaterial from the customer’s perspective.

For such cases, use this expedient to save time by skipping the evaluation of whether the promise is a performance obligation.

Next, consider shipping and delivery activities.

Refer to the following treatment under US GAAP:

When shipping and handling activities occur after the customer gains control of the goods, the seller is providing a service related to the customer’s asset. Generally, these delivery activities are considered promised goods or services (performance obligations).

However, the practical expedient in US GAAP allows companies to treat these activities as fulfillment costs rather than performance obligations, providing an option in accounting policy.

Source: 606-10-25-18A, 606-10-25-18B

25-18A An entity that promises a good to a customer also might perform shipping and handling activities related to that good. If the shipping and handling activities are performed before the customer obtains control of the good (see paragraphs 606-10-25-23 through 25-30 for guidance on satisfying performance obligations), then the shipping and handling activities are not a promised service to the customer. Rather, shipping and handling are activities to fulfill the entity’s promise to transfer the good.25-18B If shipping and handling activities are performed after a customer obtains control of the good, then the entity may elect to account for shipping and handling as activities to fulfill the promise to transfer the good. The entity shall apply this accounting policy election consistently to similar types of transactions. An entity that makes this election would not evaluate whether shipping and handling activities are promised services to its customers. If revenue is recognized for the related good before the shipping and handling activities occur, the related costs of those shipping and handling activities shall be accrued. An entity that applies this accounting policy election shall comply with the accounting policy disclosure requirements in paragraphs 235-10-50-1 through 50-6.

Similar recognition is allowed under Japanese standards.

Often, shipping costs will be recognized as related expenses.

(3) Performance Obligations Satisfied Over Time

(Short-term construction contracts and custom software)

For short-term construction contracts and custom software, recognize revenue when the performance obligation is fully satisfied rather than over time (Implementation Guidance 95, 96).

This allows recognizing revenue at a single point in time for short-term construction or custom software contracts, even if they meet over-time criteria.

The term “short-term” isn’t strictly defined, but typically means around three months, though it can vary. Consult with auditors for specific situations.

This is useful in Japan where short-term construction contracts are common, and prior standards also allowed recognizing revenue at a point in time for such contracts.

(Maritime Transport Services)

For maritime transport services recognized over time, if the period from the ship’s departure to its return is a typical duration, treat the voyage as a single performance obligation and recognize revenue over that period.

In maritime transport, handling multiple customers’ cargo on one voyage usually requires identifying transport services for each customer as separate performance obligations.

However, this practical expedient allows treating the voyage as a single performance obligation and recognizing revenue over the voyage period.

Accounting standards don’t specify a “typical duration” for a voyage.

However, Japanese corporate tax law permits recognizing revenue on the voyage completion date if the voyage duration is within four months, reflecting typical voyage durations in international routes. Thus, practice often refers to this four-month period.

(4) Performance Obligations Satisfied at a Point in Time

For domestic sales, if the period from shipping to the transfer of control to the customer (e.g., upon inspection) is a typical period (reasonable based on shipping and delivery time), recognize revenue at a point in time (e.g., shipping or delivery).

Determining whether to recognize revenue at a point in time or over time is crucial and often time-consuming.

Even for simple shipments, thorough review might be needed depending on contract terms.

However, this Japanese practical expedient can save significant time.

For domestic sales, if the period from shipping to control transfer is typical, recognize revenue at shipping.

Reasons for this expedient:

– Most domestic deliveries take 1-3 days (excluding remote islands).

– If the period is typical, recognizing revenue at shipping often isn’t materially different from recognizing it upon control transfer.

Note that this expedient isn’t available for export transactions, aligning with IFRS and US GAAP.

(5) Progress Measurement for Performance Obligations

(Initial cost recovery method in early contract stages)

For performance obligations satisfied over time, if you can’t reasonably estimate progress of satisfaction regarding performance obligation early in the contract, don’t recognize revenue until you can reasonably estimate progress.

This alternative approach exists because early-stage costs are usually immaterial, and not recognizing revenue early doesn’t significantly impact financial statement comparability. The “early stage” isn’t strictly defined but generally means within three months. Costs incurred should be immaterial during this period.

(6) Allocating Transaction Price to Performance Obligations

(Using the residual approach for immaterial goods or services)

When you cannot directly observe the standalone selling price of a good or service that forms the basis of a performance obligation, and the good or service is incidental and considered immaterial in the contract, you can use the residual approach outlined in paragraph 31(c) to estimate the standalone selling price.

You can apply this alternative treatment (the residual approach) when the good or service is incidental and considered immaterial.

The residual approach is a method with lower administrative burden, but it might not distribute profit amounts equally across multiple performance obligations. Therefore, it is limited to cases where the items are considered immaterial.

(7) Combining Contracts, Identifying Performance Obligations, and Allocating Transaction Price

(Unit of account for revenue recognition and price allocation based on individual contracts)

If both (1) and (2) are met, don’t combine multiple contracts; recognize revenue based on individual contract amounts:

1. Individual contracts with customers reflect substantive transaction units.

2. The amounts for goods or services in individual contracts are reasonably determined and not significantly different from standalone selling prices.

IFRS 15’s principles on combining contracts, identifying obligations, and price allocation can be complex. This Japanese practical expedient simplifies it, reflecting the legal and practical realities of Japanese contracts, reducing burdens.

Japan is a nation governed by the rule of law, and contracts represent agreements between companies and customers, carrying legal responsibilities for their execution. Therefore, contracts possess objective rationality. This reasoning suggests that recognizing revenue and allocating transaction prices based on individual contracts without combining multiple contracts should be permissible. This approach aims to avoid placing excessive burdens on companies reasonably.

While this argument has some validity, Japan is not the only country governed by the rule of law. Additionally, unconditionally allowing such contract-based allocations could significantly diverge from IFRS or USGAAP.

Thus, two conditions are imposed.

If these conditions help simplify complex calculations without causing significant deviations from the principles, it would benefit preparers, auditors, and users.

(Revenue Recognition for Construction Contracts and Custom Software Development)

For construction contracts and custom software development, if combining multiple contracts (including contracts with different customers or those signed at different times) to reflect the actual transaction unit agreed upon by the parties does not result in significant differences in the timing and amount of revenue recognition, these contracts can be combined and identified as a single performance obligation.

The standard treatment under the new revenue recognition guidelines allows combining contracts only with the same customer (including related parties). However, this alternative approach permits combining contracts with different customers.

For example, in construction projects for office buildings, when the main contractor also undertakes interior work for tenants other than the main project client, these are treated as separate contracts under standard practice because the customers are different.

However, this practical expedient allows combining these contracts (both the main project client and the tenants client) for revenue recognition purposes.

This treatment respects the traditional practices under Japan’s accounting standards.

Nevertheless, the use of this expedient is limited to cases where differences in the timing and amount of revenue recognition between the standard and the expedient methods are insignificant. When recognizing revenue over a certain period based on progress, this difference might significantly impact the calculations. Therefore, careful consideration, including whether one of the contracts can be deemed insignificant, is necessary.

(8) Other Specific Issues

(Monthly meter reading-based revenue recognition for electricity and gas)

For electricity and gas, estimate revenue from the meter reading date to the end of the reporting period based on the distribution volume from the start to the end of the month, proportionate to the days. Use the previous year’s average unit price for the same month.

This simplifies monthly meter reading-based revenue recognition for these industries.

(Paid supply Transactions)

In a paid supply, if a company has no obligation to repurchase supplied goods, recognize the disposal (write-off) of the supplied goods but not the revenue from their transfer. If there is an obligation to repurchase, don’t recognize either the revenue from transfer or the disposal. In a non-consolidated standalone financial statements, recognize disposal at the time of transfer.

In Japan, transactions supply for a fee (Paid supply) are common, especially in the automotive industry.

Paid supply refers to transactions where a company transfers raw materials (referred to as “supplied items”) to an external party (referred to as the “recipient”) for a fee, and then purchases the processed supplied items (including those incorporated into finished products) from the recipient.

In the automotive industry, companies like Toyota and Nissan often request subcontractors to manufacture parts. This sequence of supplying parts to the subcontractor and repurchasing them is known as paid supply.

In a typical paid supply arrangement, the company sells the materials to the subcontractor with a certain profit margin and then buys back the processed parts. The accounting issues here are: (a) whether the main contractor can recognize revenue from the sale of parts to the subcontractor, and (b) whether the contractor can recognize the disappearance of the material inventory.

The answers are: (a) the main contractor does not recognize revenue, and (b) the recognition of inventory disappearance depends on the presence of a repurchase obligation.

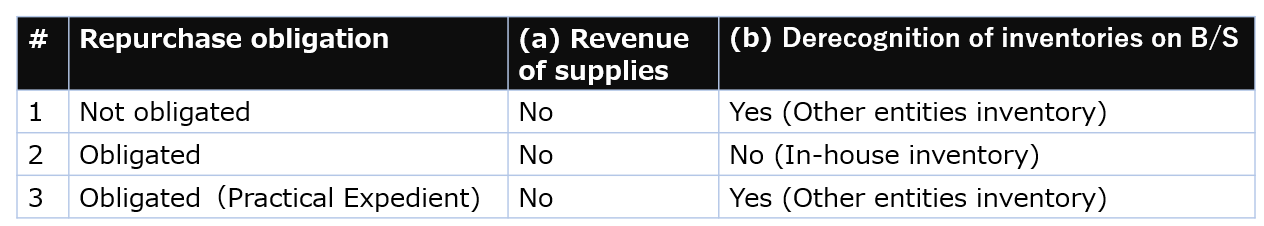

This point can be summarized as follows. #3 is a special treatment in the standalone non-consolidated financial statements.

When there is a repurchase obligation, the inventory has not transferred, and the main contractor should record it. However, since the inventory physically resides with the subcontractor and the subcontractor manages it, the main contractor must obtain inventory information, which is practically challenging as noted by the automotive industry.

Therefore, in standalone financial statements (not consolidated ones), a practical expedient (#3) is allowed.

Please note that this expedient is only permitted for standalone financial statements of each entity, which is linked to corporate tax filing.

Please also note that paid supply can take various forms and have different realities. Therefore, it is essential to make appropriate decisions in consultation with the audit firm.